- Home

- William H. Lovejoy

Phantom Strike Page 2

Phantom Strike Read online

Page 2

“We need drop tanks installed on that first F-4E,” Demion pointed out.

“Also,” Kriswell added, “we need to rob a couple planes for two drag chutes, a replacement IFF for 1502, and a rear canopy for 925.”

“Of course. It’s not a problem.” Dinning turned his head toward Wyatt. “Do you mind my asking what you’re going to do with these planes?”

“Not at all. Back in ’61, the Phantom held some world records for speed at Mach 2.6 and for altitude at ninety-eight thousand feet. It’s still a good airplane, Captain, and we’re going to modify these for racing and endurance trials, as well as taking them on the air show circuit.”

“I see. I wish you luck, but do you need all of these electronics?”

“Hell, if I’m buying them, I might as well get what comes with them, right?”

The set of Dinning’s mouth suggested he thought otherwise. “Yes. I suppose so.”

“Thanks. Now, I’d appreciate it if you could get them all towed in in the morning and checked out. We won’t worry too much about avionics at this point, but we do need batteries installed on almost all of them, and battery charges and fluid levels will have to be up to par. I’d like to have everything fuelled and ready to go by the day after tomorrow.”

The captain straightened up in his chair, his face apologetic. “On Thursday? I’m afraid that won’t be possible, Mr. Cowan.”

“The aircraft we selected shouldn’t pose many problems, Captain.”

“Not on the flight readiness, no, sir. However, before surplus aircraft can be sold to civilians, we are required to have our ground crews remove a number of weapons-related systems: the ordnance pylons, the cannon, threat warning devices, jammers, chaff dispensers, attack radar, and the like. I’m sure you understand, sir. None of that would be necessary for your objectives, anyway.”

While Dinning was explaining his problem, Wyatt got out his wallet and withdrew a certified check for $225,000. The check was identified as issued in favour of Noble Enterprises, Inc., of Phoenix, Arizona. He placed it on the table and slid it across to Dinning.

“What’s this, sir?”

“That’s payment for seven aircraft, Captain. And I’ll give you another check for the fuel and whatever maintenance is required.”

From the look on his public relations face, Dinning apparently did not think that some twenty million dollars’ worth of aircraft should be surplused to some civilian at a penny to the dollar.

“Well, sir, I think the surplus material people will want to negotiate a little further.”

“The price has already been approved by the Department of Defence,” Wyatt explained to him.

“Oh. I didn’t know that, Mr. Cowan.”

“And the price includes all equipment now aboard the airplanes. We get them as is.”

Dinning stood up, the resolution to prevent civilians access to sophisticated, and possibly still classified, military weapons clearly revealed on his face. “I’m going to have to check on that, Mr. Cowan.”

“I know. That’s why I gave you the phone number.”

Two

Andrew Michael Wyatt’s hair was full over the ears, tapered above his neck, and fell across his forehead in a casual swoop. With the deep tan of his face, he might have been a Malibu Beach or Honolulu surf bum in appearance. The deep etching at the corners of his ice-blue eyes and his firm mouth suggested otherwise. He did not smile very often, and his closest friends sometimes found him short on humour. What really killed the leisurely image was the iron grey colour of his hair.

Though he was only in his mid-forties, Wyatt impressed people as being a little older and a little wiser, maybe fifty. He had lived with the overly mature image for twenty years, having gone prematurely grey at twenty-four. He could, in fact, pinpoint the date when the silver began to appear in previously dark locks.

It was April 17, 1970, a few hours before April 18.

It was a night mission over Haiphong, and he was flying an F-111A swing-wing fighter bomber under development by General Dynamics. Wyatt was assigned to the 428th Tactical Fighter Squadron out of Ubom in Thailand, and the squadron had been given six F-lll’s for operational trials over North Vietnam. The early version of the aircraft was disappointing for they lost half of their complement within a month.

His was one of them.

Armed with two 750-pound bombs, Wyatt’s airplane had been given a dock and warehouse in the harbour as primary targets. Military intelligence had determined that both the dock and the warehouse were supposed to be military targets rather than civilian. Targets were very specific in that war, approved by the White House inner circle — all of whom considered themselves military experts, and anything not adorned with some kind of NVA insignia, whatever that might be, was off-limits.

He and his wingman, a second lieutenant named Ruskin, approached the harbour low from the west, riding the hilly terrain as low as possible in order to avoid radar detection. They were accompanied by a flight of four Marine F-4s flying cover. As they neared the city, Wyatt and Ruskin climbed to five thousand feet and spread a quarter-mile apart in search of their mission objectives on the far side of the anchorage. His Weapons System Officer, Miles Adair, in the seat next to him, had his head buried in the radar boot.

Wyatt never reached, nor saw, either of his own targets. Five miles before reaching the harbour, the radar screen lit up with the blips of Fan Song target-seeking radars. Adair counted off six surface-to-air missile launches. Most of the Fan Songs went passive as the missile-carrying F-4 fighters launched retaliatory strikes against the radar installations. As the harbour finally burst into view, the dark skies were peppered with bright pinpricks of light: exploding SAMs and erupting antiaircraft shells from the quad-barrelled ZSU-23 batteries surrounding Hanoi and Haiphong.

Some brave communist radar operator kept his set active in order to guide his missile, and Wyatt’s earphones sang with the pitched tone of the threat warning and Adair’s verbal additions to it.

“Lock-on, Andy! Break right!”

Checking his rear-view mirror, he saw the flare of rocket exhaust circling the dark hole of the missile body, and he jinked the plane hard to the right, climbing, but could not lose his deadly pursuer.

The missile went right up his starboard tail pipe.

And did not detonate. It was a Soviet Union version of a dud.

The aerial collision still disintegrated his right Pratt and Whitney TF30, shredding the fuselage and wing with snapped turbine blades. The F-lll skidded and bucked, then started vibrating violently. Red warning lights lit up the instrument panel like the Las Vegas Strip. He killed power on the right engine. A quick stab at the transmit button told him he had lost his radios. Vital electrical and hydraulic arteries had been severed.

Wyatt jettisoned his bomb load and his drop tanks in the middle of the harbour and retarded the port throttle, which eased the vibration. Making a slow 180-de-gree turn, he limped the airplane back to the west as far as Laos. Ruskin stayed with him all the way and circled when Wyatt could no longer keep the F-lll airborne, and he and Adair ejected over a rice paddy. They were picked up by helicopter within an hour, and Wyatt woke up the next morning with the first strands of grey showing at his temples.

He was fully grey-headed by the end of 176 missions and his third tour.

On Thursday morning, he was up by five-thirty to run through his twenty minute regimen of sit-ups, push-ups, and deep-knee bends. Wyatt’s six-foot frame of hard muscle was probably in better shape than it had been twenty years before, but it took increased effort to keep it at the level he wanted. After exercising, he showered, washed his hair, and shaved. It took him five minutes to dress in slacks and a blue sport shirt and to pack his single carry-on bag. Wyatt carried the small bag and the larger one containing his flight gear down to the Holiday Inn’s desk and checked out, paying in cash. Everyone was supposed to pay in cash. He bought a copy of the Phoenix Gazette and went looking for breakfast.

Barr was already in the coffee shop, working away at four eggs and two breakfast steaks. He grinned as Wyatt took the chair opposite him. “Morning, boss.” Wyatt poured himself a cup of coffee from the insulated plastic pot on the table. “You look amazingly alive. How was Nogales?”

Bucky Barr and two of the others had crossed the border the night before to analyse the current level of Mexican revelry.

He reported, “In a world of change, Nogo doesn’t. Same varieties of debauchery.”

Wyatt ordered an omelette guaranteed to contain extra jalapeno peppers and read the paper while he waited for the rest of his team. From Tokyo to Beirut to Washington, the world was in typical disarray. A little greed, a little power-grabbing, a lot of fanaticism.

By six-thirty, they had all stacked their soft-sided luggage in the lobby and were gathered at two tables, urging their beleaguered waitress to greater speed. In addition to Barr, Demion, and Kriswell, there were four more faces. Norm Hackley, Dave Zimmerman, Cliff Jordan, and Karl Gettman had flown in commercially from Albuquerque the previous afternoon. Hackley and Gettman were the two Barr had cajoled into joining him for his Mexican spree. Both were droopy-eyed this morning and particularly fond of ice water and orange juice.

Zimmerman, a clean-cut, sandy-haired man of twenty-eight, was the youngest pilot in Wyatt’s group. He had been an F-15 Eagle jockey for the USAF until eighteen months before. He leaned toward Wyatt’s table and said, “Beats the hell out of me, Andy, why these old fossils, who are supposed to be wise veterans of life, can’t grasp some simple truths. I’ve learned that there’s a direct correlation between the night before and the morning after.”

“Go flub a duck, Davie boy,” Gettman muttered.

Barr, who was never affected by mornings-after, said, “The truth, Dave, is that the night before is worth the morning after.”

“Selfish bastard,” Gettman told Barr. “You always speak for yourself.”

“I knew there was a truth in there, somewhere,” Norm Hackley said, “but I think it’s only a half-truth.”

“Do you guys realize you all sound incoherent?” Wyatt asked.

“Now, there’s a truth,” Zimmerman said.

“You should have heard them last night, you want incoherence,” Barr said.

“I especially don’t want incoherence today. I want bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.”

He got nods in response, but some of them seemed half-hearted.

Wyatt folded his paper and surveyed his group. All of them were employees of his Aeroconsultants, Incorporated, and he was fond of them all. Except for Zimmerman and a few of the technicians back in Albuquerque, he had served Air Force time, somewhere in the world, with all of his people.

After the waitress had brought yet two more coffeepots, Wyatt briefed them. “Bucky, Cliff, and I will take the F-4Es. Jim, you get the Herc, and Tom will ride in the right seat for you.”

Demion had multiengine and jet ratings on his private license, though he had never flown for the military except as a peripheral activity in consulting for them. His interest was secondary to his profession of aeronautical engineering.

Kriswell was not a pilot. He had abandoned pursuit of a flying license after his first landing on his first solo flight in a Cessna 182. He had managed to leave part of the propeller and the landing gear a few hundred yards away from where the airplane finally came to rest.

“You get to handle the Thermos, Tom,” Demion said. “No touching the yoke.”

“Can I play with the throttles?”

“If you’re real good,” Demion promised.

“The rest of us are here to sightsee?” Hackley asked. “Nope,” Wyatt told him. “I only pay you to work. I’ve got a couple F-4Ds for Dave and Karl. Norm, you get a C model.”

“Shit. The slowest one of the bunch, no doubt. Anybody want to flip a coin?”

“No trades. The hydraulics are a little iffy on your bird, Norm, and if there are any problems, I want your experience in the cockpit.”

Mollified, Hackley — who had F-4 combat hours — shrugged and said, “Ho-kay.”

“Our destination is Ainsworth.” Wyatt had not mentioned that to any of them before.

“What the hell’s an Ainsworth?” Barr asked.

“And where in the hell is it?” Hackley added.

“It’s in north central Nebraska. Just under a thousand miles, and we can make it in one hop.”

“Nebraska in mid-July?” Barr complained. “You’ve got to be shitting us, Andy.”

“The sandhill cranes like it.”

“Yeah, but I’ll bet the crane population is composed of two genders,” Barr said.

After the last of the coffee was drained from their cups, the group made last pit stops and then carried all of the luggage out into the dry heat of morning and dumped it into the trunks of two taxicabs. Thirty minutes later, they hauled it into the operations office at Davis-Monthan and stacked it against a wall opposite the counter.

Wyatt figured that all of the right telephone calls had been made and most of the objections overcome because he could see his seven aircraft lined up on the tarmac about a quarter-mile away. A fuel truck, three start carts, several pickups, and a dozen men were clustered around them.

They waited, milling around, hitting the Coke machine.

Captain Dinning arrived at eight-fifteen wearing a haggard smile and carrying a four-inch-thick folder. He dropped it on the counter and said, “You don’t know what I’ve been through in the last twenty-four hours, Mr. Cowan.”

“I’ve got a fair idea, Captain. And all of it in quadruplicate, too.”

Bucky Barr asked, “Did we get all of the tail numbers we asked for?”

“That’s correct.”

“I’ll get a couple of the guys, and we’ll start filling out flight plans. Jim went off to get the weather info.”

“Good. I want the Hercules to go first, followed by a flight of the 4Ds and the C model. The rest of us will fly out last.”

“And get in first, no doubt,” Barr said.

Barr, Gettman, and Hackley went to the end of the counter and began to fill out forms.

Dinning opened his folder and, one by one, began laying multipart forms in front of Wyatt. He saw that ownership had been vested in Noble Enterprises, Phoenix, Arizona, as requested. With his ballpoint pen, Wyatt dated and signed each form as Roger A. Cowan, President, Noble Enterprises. He was given copies of receipts, temporary registrations, temporary FAA certifications, and, on the F-4E fighters, temporary registrations for the M61A1 twenty-millimetre multi-barrelled cannons.

“The understanding is that you’re to contact the Treasury Department’s firearms division and arrange for a hearing on those,” Dinning said.

“You bet,” Wyatt said, but did not think he could fit it into his schedule.

“That’s what caused the most trouble,” Dinning told him. “Even the base commander got involved.”

And lost, Dinning guessed.

“And finally agreed, if the M61s were disabled.”

“How was that accomplished?”

“The fire control black boxes have been removed,” the captain told him.

“Where are they?”

“On board the C-130.”

“Okay. That’s safe enough.”

“One other thing,” the captain said. “With those radios. You’re supposed to stay off military frequencies.”

“I don’t like to listen to Eagle pilots, anyway,” Wyatt assured him. He signed a sheet promising just that.

“Then, we have this.”

Wyatt took the statement from Maintenance and Operations and went over the entries. Two tires had been replaced. Four sets of brakes were new. The avionics and basic instruments had been superficially examined and temporarily okayed. There were labor charges for installing a rear canopy on 925. Every engine had been started and run for fifteen minutes, but there were no guarantees. Fuel tanks, including external tanks, had been topped off. He had been char

ged for nearly eighty gallons of lubricants and hydraulic fluids.

The billing came to $34,292.67.

His guess had been close to right. Wyatt produced another certified check for thirty thousand, and wrote out a company check for the balance. Both checks were written against Noble Enterprise’s Phoenix account. It was an account that would cease to exist as soon as this last check cleared.

“Does that make us even, Captain?”

“I believe it does, Mr. Cowan. Happy racing.”

The captain did not believe the racing angle for a minute, Wyatt thought. “Thanks. And thanks for your help.”

“Anytime, sir.” Dinning turned and left.

Barr came over to him. “We’re all filed. You need to sign your flight plan.”

After he signed off on a flight plan that hinted at a destination in Montana, Wyatt led his team down to a dressing room, and they changed into flight gear. Their flight suits were identical, dove grey in colour, with their first names stitched in red over the right breast pockets. Across the back of each garment, red letters advertised, “NOBLE ENTERPRISES-AVIATION DIVISION.” Demion and Kriswell left their matching helmets and their parachute harnesses in their duffel bags, but the rest of them hoisted chutes over their shoulders and carried their helmets, G suits, personal oxygen masks, duffel bags, and over-nighters. In a group, they left operations and crossed the hot concrete of the apron toward the parked aircraft. The short walk resulted in sweat-darkened armpits. Wyatt could feel the perspiration dripping down his back.

“Don’t you feel like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, heading down the main drag in Tombstone?” Barr asked.

“As a matter of fact, no,” Wyatt told him.

“We’ve got to work on your imagination, Andy.” The excess luggage was stowed in the crew compartment behind the cockpit of the Hercules.

Everyone found his airplane and spent the next hour going over it with the crew chief who had worked on it. When each of the pilots had expressed to Wyatt his relative satisfaction, Wyatt said, “Looks like a go, then. Jim, you and Tom can fire up.”

Ultra Deep

Ultra Deep Phantom Strike

Phantom Strike Delta Blue

Delta Blue Alpha Kat

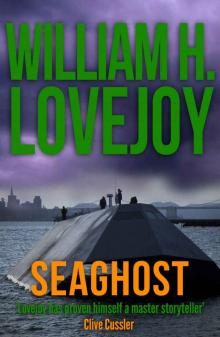

Alpha Kat Seaghost

Seaghost